Chile's textbook mine rescue brings global respect

SAN JOSE MINE, Chile – Chile's 33 rescued miners posed with the president and were poked by doctors on Thursday, itching to reunite with families and sleep in their own beds for the first time since a cave-in nearly killed them on Aug. 5.

Relatives were organizing welcome-home parties and trying to hold off an onslaught of demands by those seeking to share in the glory of the amazing rescue that entranced people around the world and set off horn-blowing celebrations across this South American nation.

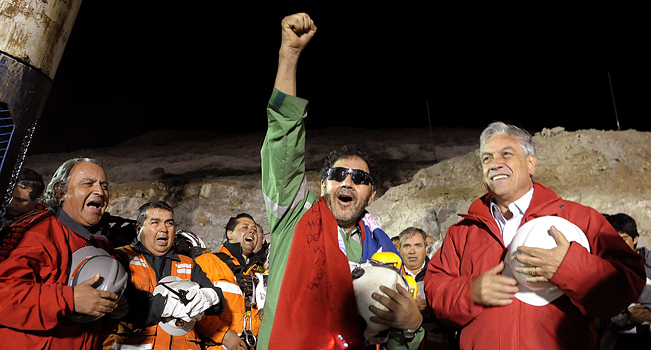

President Sebastian Pinera posed with the miners, most of whom were wearing bathrobes and slippers, for a group photo, and then celebrated the rescue as an achievement that will bring Chile a new level of respect around the world.

The miners and the country will never be the same, Pinera said.

"They have experienced a new life, a rebirth," he said, and so has Chile: "We aren't the same that we were before the collapse on Aug. 5. Today Chile is a country much more unified, stronger and much more respected and loved in the entire world."

The billionaire businessman-turned-politician also promised "radical" changes and tougher safety laws to improve how businesses treat their workers.

"Never again in our country will we permit people to work in conditions so unsafe and inhuman as they worked in the San Jose Mine, and in many other places in our country," said Pinera, who took office in March as Chile's first elected right-wing president in a half-century.

None of the miners are suffering from shock despite their harrowing entrapment, a reflection of the care and feeding sent through a narrow borehole by a team of hundreds during their 69 days trapped underground. Even a team of psychologists helped keep them sane.

"All of them have been subjected to high levels of stress and most of them have tolerated it in a truly exceptional way," said Dr. Jorge Montes, deputy director of the Copiapo Regional Hospital. "We don't see any problems of a psychological or a medical nature."

"We were completely surprised," added Health Minister Jaime Manalich. "We called this a real miracle, because any effort we could have made doesn't explain the health condition these people have today."

After weeks of fear, desperation and finally hope, the miners were pulled out one by one in a capsule that carried them through a narrow tube of solid rock — a dizzying 23-hour marathon of rescues.

The men, their eyes hidden behind sunglasses to protect from the sun and glare of lights, emerged to tears and embraces from relatives, and cheers and patriotic chants, as tens of millions of people watched on television around the world to see a joyful end to the longest known ordeal of men trapped underground.

All of them remain tense and spent a restless first night in the hospital, the doctors said, which is only natural given what they face as they begin their new lives.

For many, what they experience next may be incomprehensible at first.

Honors and offers of jobs and even vacations poured in from around the world for men who walked into a mine on Aug. 5 as workers doing a dirty job to support their children or buy a house. They were lifted out weeks later to find themselves international symbols of perseverance — as well as icons of patriotism at home.

Spain's Real Madrid football team invited the 33 to attend a game in their stadium. Chile's football federation said it would offer a job with its youth teams to Franklin Lobos, a former national team player who had later found himself driving a taxi to make ends meet before he was caught in the mine collapse. It also said it was organizing a "Copa 33" tournament in their honor.

The internationally popular Spanish language variety show "Sabado Gigante" announced it would dedicate a show to "The 33" and invited fans to suggest questions for them.

And a Greek mining company offered to fly each one, with a companion, for a week's vacation in the Mediterranean.

Pinera, meanwhile, vowed that those responsible for the mine collapse "will not go unpunished. Those who are responsible will have to assume their responsibility."

The rescue will end up costing "somewhere between $10 (million) and $20 million," a third covered by private donations with the rest coming from state-owned miner Codelco — the country's largest company_ and the government itself, Pinera said.

Mining accounts for 40 percent of the Chilean state's earnings and the rescue's details were run by its operations manager, Andre Sougarret.

The Aug. 5 collapse brought the 125-year-old San Jose mine's checkered safety record into focus and put Chile's top industry under close scrutiny. Many believe the collapse occurred because the mine was overworked and lacked such essential safety features as a reinforced escape shaft.

The families of 27 of the 33 rescued miners have sued its owners for negligence and compensatory damages. A separate suit was being prepared accusing the government of failing to enforce its safety regulations.

Also suing the San Esteban company is Gino Cortez, a 40-year-old miner who lost his lower left leg a month before the mine collapsed when a rock fell on him in an area that lacked a protective metal screen.

"This mine has to close," rescue coordinator Sougarret said Thursday.

Pinera said he will triple the budget of mine safety agency Sernageomin, whose top regulators he fired after the collapse. He also created a commission to investigate the accident and recommend changes. Some action was swift: The agency shut down at least 18 small mines for safety violations.

"The mine has been proven dangerous, but what's worse are the mine owners who don't offer any protection to men who work in mining," said Patricio Aguilar, 60, of nearby Copiapo, during celebrations of the meticulously executed rescue.

Advances in technology notwithstanding, mining remains a dangerous profession in the smaller mines here in northern Chile, which employ about 10,000 people.

Since 2000, about 34 people have died every year on average in mining accidents in Chile — with a high of 43 in 2008, according to Sernageomin data.

Most of the rescued miners live in Copiapo, a gritty, blue-collar city surrounded by the Acatama desert. Copiapo's central plaza was jammed with thousands of revelers watching the operation on a giant screen as street vendors hawked Chilean flags bearing the faces of "Los 33."

The last miner, shift foreman Luis Urzua, emerged from the Phoenix rescue capsule after the 2,041-foot 622-meter) ascent to a joyous celebration.

With hardhats held to their hearts, Urzua and the president led the rescue team in singing the national anthem. Broadcast by state TV, it seemed ubiquitous in small country of 16 million roiling with pride.

The rescue exceeded expectations every step of the way. Initially, officials said it might be December before the men could get out. Once the drill that opened the escape shaft pierced the men's subterranean prison, they estimated it would take 36 to 48 hours to get everyone out.

The actual time: 22 hours, 39 minutes.

The only real glitch was indeed minor — it became bit difficult to open and close the escape capsule's door as the day wore on, said Laurence Golborne, the mining minister who Pinera put in charge of the rescue. Early Thursday morning, the last rescuer who helped the miners into the escape capsule came up safely to end the operation.

Golborne has won high marks for his deft management of the closely scrutinized rescue, and Chilean media have been abuzz with discussion of him as Pinera's most likely successor. Elected in December 2009 to a four-year term, Pinera is constitutionally barred from running again.

Chile has promised to care for the miners for six months at least — until they can be sure each man has readjusted.

Psychiatrists and other experts predict their lives will be anything but normal.

Previously unimaginable riches awaited men who had risked their lives going into the unstable mine for about $1,600 a month.

At some point, the men will need to decide whether they will return to the mines.

Many of their relatives are dead-set against it, but they also acknowledged that they probably couldn't stop the miners from going down again.

Mario Medina Mejia, a local geologist, said plenty of Chilean miners have returned underground after close calls, and he compared it to sailors who survive shipwrecks only to ply the waves again.

"If they need the work they will return to the mine," he said. "It's their life, their culture, the way they make their living."

___

Reposted From AP

No comments:

Post a Comment